Venture capital company Andreessen Horowitz (a16z) recently introduced a series of “Can’t Be Evil” licences that let creators grant NFT owners partial or near-complete rights to NFT art.

Last month, a study published by The Galaxy examined the top 25 most valuable NFT projects and found that, despite many projects acknowledging that NFTs transferred either the copyright or the license in the original work, only 1 in 25 of those projects even attempted to do so. However, now the VC company Andreessen Horowitz (a16z) is trying to change that.

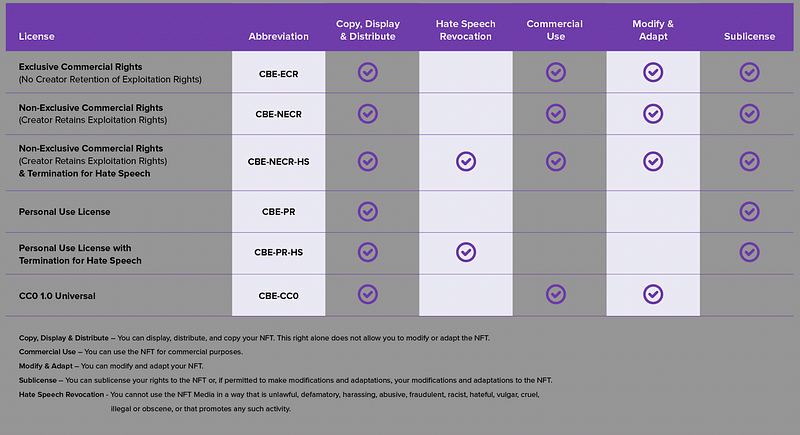

The “Can’t Be Evil” licences, named after a common claim about blockchain businesses, are designed to be comparable to the Creative Commons (CC) copyright framework. The significant difference is that 16z’s licenses regulate the relationship between an NFT buyer and the person who created the original art it is linked to. They can be freely used by any project creator, and provide a range of different approaches for NFT projects: from limited personal use terms to broader licenses that let anyone use the artwork for any purpose.

The company’s General Council, Miles Jennings, wrote that the licenses have been tuned for decentralized Web3 projects to remove ambiguity, minimise confusion around IP rights grants, and avoid future legal troubles.

For the licences to function with the Web3 world, the VC company asked Punk6529 — a crypto influencer known for his valuable collection and insightful Twitter threads — to help shape them. Furthermore, they released the license terms for free via an open-source, Creative Commons Zero (CCO) license, meaning that they can be freely used as Web3 creators see fit.

The broadest license is a direct copy of the CCO agreement, and lets anybody remix or redistribute a piece of art. “Exclusive Commercial Rights” gives the buyer an exclusive right to use the art as they want to. “Non-Exclusive Commercial Rights” is similar, but the NFT creator retains the right to use the art as well. There’s also a version of the non-exclusive commercial license that gets revoked if the NFT is used for hate speech — a category that includes defamation, harassment, fraud, or “vulgar, cruel, illegal, or obscene” uses. There are also two “Personal Use” licenses, which let people copy and display art but not use it commercially. One includes the hate speech agreement, the other doesn’t.

The licences also tap into the question of sublicensing: how can an NFT holder authorise someone to use the art on something like a coffee mug, and what happens to that contract if they sell the NFT. The licences say that new buyers don’t get an NFT that’s already tied up in deals with other people. The contract also specifies that copyrights only transfer if the NFT is legally sold, not stolen.

At this point it all sounds quite positive, right? But there are a few problems with “Can’t Be Evil” licences that begin with sublicensing. It’s fine and not unusual that a buyer of a Bored Apes NFT could license the media to be featured to a film studio, for instance. But given that NFTs can be sold or stolen in a whim, this creates a great deal of uncertainty for those trying to obtain and exploit those sublicenses. The are no revocation terms for sublicensing, which can result in serious issues.

Secondly, there is no “All Rights Reserved” option. With NFTs it can’t be treated as default as there’s often an assumption of some rights transfer, making it necessary in this case. Another is the issue of hate speech. The hate speech revocation clause doesn’t just cover hate speech, in addition it covers language that is, “vulgar, fraudulent, illegal or obscene.” But who is there to determine what “hate speech” is under this license? If the creator and the creator alone determines what is hate speech, and the license is irrevocable by creators, this exception can be triggered at any time.

Finally, these licenses are limited to copyright only. This means that connected rights may not transfer. These issues are shared between CBE and Creative Commons licenses. However, one gaping hole in the CBE license structure is the lack of handling of moral rights. The CBE licenses don’t mention moral rights at all. This raises serious questions about what happens when and if moral rights and the rights granted by a CBE license collide.

The a16z idea and execution are both interesting and very promising. Considering other attempts by Creative Commons at making a standardised NFT license have not been a full success in the non-crypto world. But it’s difficult to draft copyright licenses that are easy to understand, international and applicable to a wide variety of works. Simply put, licensing and transferring copyrighted works is hard in itself, but if you mix in the complexities of NFTs, things get really challenging. Let’s observe how the story evolves.