From 1836 to 1864, Wildcat Banking prospered in some states of the U.S.

The history and characteristics of this lawless banking system mirror that of cryptocurrencies, especially stablecoins. Will they have the same end?

Wildcat Banking

Following independence in 1776, the United States tried to create a central entity to manage all the nation's financing issues. By 1836, however, the charter of the Second Bank of America was allowed to expire, and monetary regulation went back to the hands of individual state authorities.

Free banking laws were adopted in several places. Professor Gerald P. Dwyer Jr., an ex-director at the Federal Reserve Bank of America, explains that this type of regulation "opened up note issuance to limited-liability organizations without discretionary approval by a legislature."

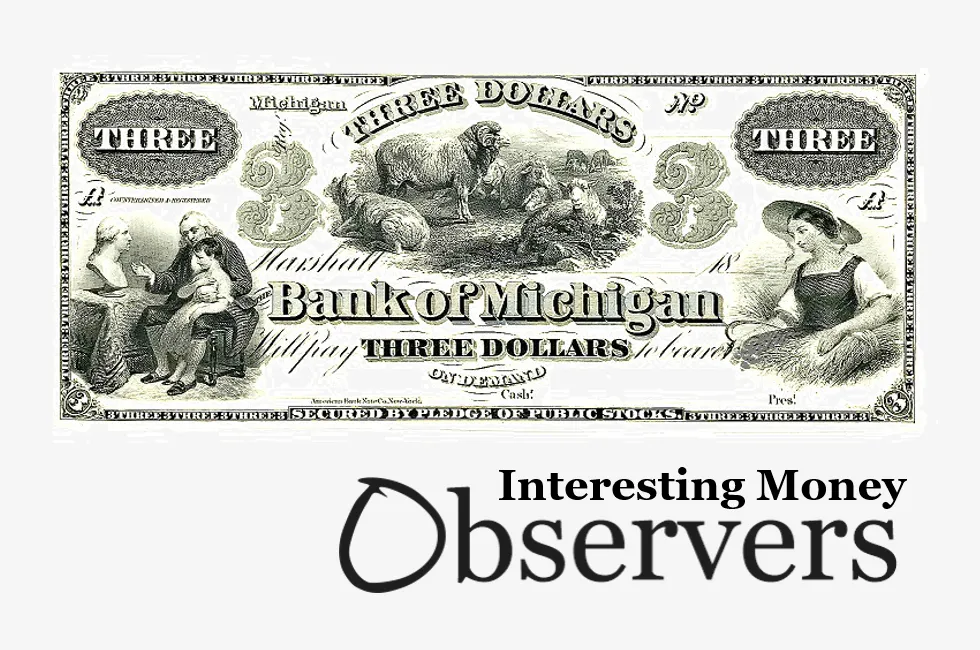

States' legislation was fewer and diverged significantly across borders. In Michigan, free banking laws led to Wildcat Banks—financially unsound banks that popped up in inaccessible locations where "wildcats roamed."

Nowadays, any institution wanting to be a money issuer must fulfill endless requirements and have significant capital. In Michigan in 1836, all it took was a minimal security deposit with the state banking activity consisting of bonds - that could include personal bonds - and mortgages - which could easily be inflated.

Given the little to no location restrictions and the very few capital requirements, there was a surge in free-banking establishments, leading to a plethora of different currencies being used in daily transactions. According to William Graham Sumner, a social scientist of the time:

"There were hundreds of banks whose notes circulated in any given community. The "bank note" were bits of paper recognisable as a species by shape, colour, size and engraved work. Any piece of paper which had these appearances came with the prestige of money; the only thing in the shape of money to which the people were accustomed."

The testimony of Summer continues:

"The person to whom one of them was offered, if unskilled in trade and banking, had little choice but to take it. A merchant turned to his “Detector.” He scrutinized the worn and dirty scrap for two or three minutes, regarding it as more probably “good” if it was worn and dirty than if it was clean, because those features were proof of long and successful circulation."

The Dangers Of Having Private Money In Circulation

Wildcat bankers were in business for a good time, not for a long time.

"The increase in the number of banks in Michigan was large, and their openings were quickly followed by their demises."

The few laws that existed were difficult to enforce, and it was equally challenging for state authorities to verify the soundness of the deposits made by bank owners with the states' banking authority.

"Banks were at best franchises of subnational state government alike, and at worse franchisees of themselves. Their notes were their own liabilities - hence liabilities of private issuers," notes Robert C. Hockett from the Cornell Law School.

The flawed system led to the proliferation of "fabulous stories of fraudulent activity." Combined with the difficulties of having up-to-date information typical of the 19th century, it resulted in a status quo in which people didn't trust money.

Bank notes were exchanged at a discount depending on the issuing bank's perceived level of risk. Estimates collected by Professor Dweyer Jr. suggest that note holders' losses were between 30 and 60 percent of the par value of all Wildcat bank notes.

Bray Hammond, a financial historian who lived through that period, believed that in some of the states where free banking laws were a colossal fiasco, people would have been better off without any banks at all.

WildCat Banks As Precursors Of Stablecoins

"While the technology underlying cryptocurrencies is new, the economics is centuries old," noted economist Gary Gorton and U.S. Federal Reserve attorney Jeffery Zhang in a paper entitled "Taming Wildcat Stablecoins."

Like wildcat banks, stablecoins are currencies backed by privately owned assets that assume the position of a fiat currency. They are not controlled by a central authority, and the 'stable' in their names is merely a suggestion. The ease of creating stablecoins has resulted in incredibly diverse markets, and the lack of regulatory oversight over them has resulted in several "fabulous stories of fraud."

But are, like wildcat banks, stablecoins destined to be extinguished?

When the Civil War started in 1861, the United States government quickly realized it needed to create a singular entity that controlled the monetary system and develop a singular currency—the dollar—to minimize the risk in daily transactions.

The National Bank Act of 1863 put banks under federal control, and in 1964, it began to tax the issuance of private monies, quickly ending the Wildcat banking era.

So, too, after the Terra/Luna crash in 2022 and the subsequent disclosure of unscrupulous behavior by crypto CEOs, governments worldwide began to regulate cryptocurrencies.

The MiCA regulation entered into force in the E.U. last month, and a bipartisan bill to regulate stablecoins has recently been introduced in the U.S.

Due to stablecoins' notorious benefits in improving transaction flow, central banks have been studying, testing, and launching their own versions of digital currencies with parity with national fiat currencies.

With regulation making stablecoin issuers' activities less profitable and CBDCs offering risk-free competition, the role of stablecoins as a means of payment is under attack by state intervention, much like wildcat banking was.

We are, however, not in the 19th century.

Today's markets are global, not national, and the pace of technology beats that of bureaucracy. Stablecoins' independence of geography is what first made them thrive, and it might as well be the trump card that allows them to succeed where others have failed.